Tackling issues like disability are difficult, especially with children. What should parents be teaching kids about disability? How do you approach it? How do you ensure that your child is accepting and open minded toward others? What do you do when you yourself don’t have a strong understanding of the topic at hand?

The best place to find answers is the source. We spoke to Marianne Scott, a mother of three in Southern Arizona. Her 15-year-old daughter is considered severely disabled, living with cerebral palsy, epilepsy, brain damage, critical visual impairment, anxiety and an intellectual disability. It’s important to note, however, that Scott’s perspective is not all–encompassing.

People with disabilities and parents of children with disabilities cannot fit into one genre that all agrees what should and shouldn’t be taught about disability. The topic is complex, and it’s important to consider a range of opinions.

Here is one viewpoint to consider:

It’s wrong to assume people with disabilities have sad, awful lives.

There is no reason to think people with disabilities don’t experience the same joy and happiness as others. Assuming they lead miserable lives builds a barrier between them and able-bodied people. It creates an unfounded separation that has the potential to prohibit potential friendships.

Not all people with disabilities would change their circumstances if they could.

Believe it or not, some PWD actually find value in their disabilities. Sometimes what can be seen by society as a “setback” or “limitation” is actually an opportunity for new experiences to PWD.

VMI discussed this in an earlier blog post, where one man, Larry Watson, found success becoming a lawyer after his injury kept him from continuing on with sports.

People with disabilities can and should function as part of society.

Though PWD might need assistance or modifications to participate in a way similar to able bodies, they are capable of contributing to society: whether it’s in the job force, public sector, education or elsewhere. They also deserve to participate just as much as someone else, not despite their disability but because of their disability. PWD offer a unique viewpoint that must be heard if we are to create a fair and free society. Parents should teach children that having PWD in their classes and friend group is a good thing.

People with disabilities are human.

This is perhaps the most important rule. Parents must teach their children that people with disabilities are human. They may do things differently, like use a wheelchair, and they may even speak differently in some cases, but they are still human and deserve respect, friendship and love.

People with disabilities experience different challenges than able-bodied people.

Scott says this is one of the most common lessons she must teach her other children. They would often ask why their disabled sister was allowed certain privileges, like a TV in her bedroom. Scott responds by saying their sister experiences challenges just like they do. All humans experience challenges. But everyone’s challenges are different and therefore require different responses. PWD don’t get “special treatment.” They receive modified treatment appropriate to their situation.

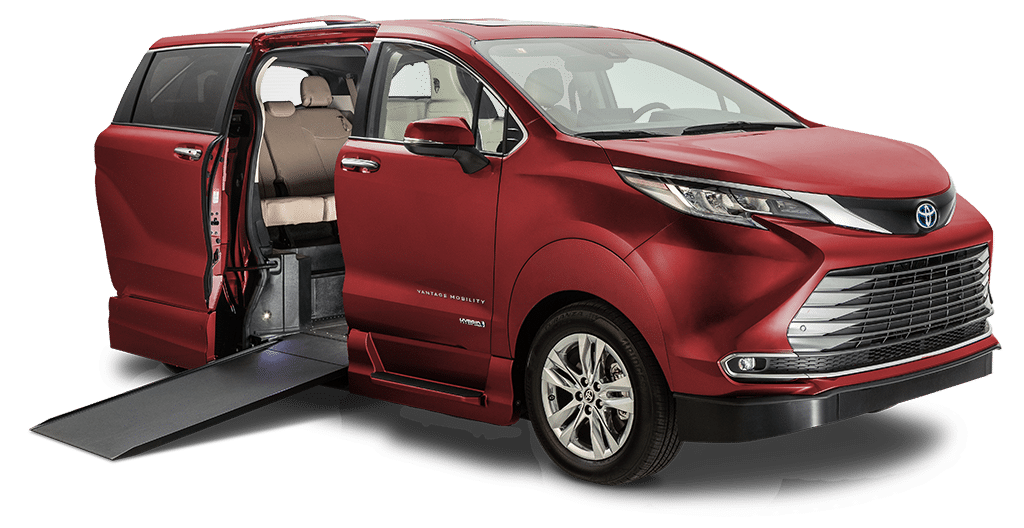

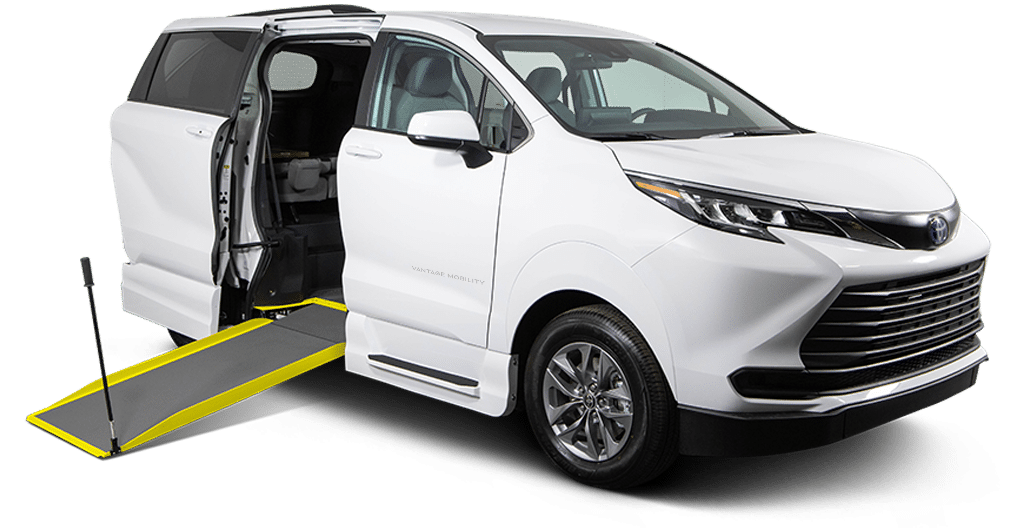

Sometimes disability influences basic life choices that able-bodied people don’t consider.

It is helpful to remind kids that PWD sometimes have to make choices because of their disability. For example, many people in wheelchairs opt to purchase wheelchair vans, or larger wheelchair accessible vehicles. This may be because it’s easier to travel with more space, it may be because caregivers have to use the van space to change diapers for those who are incontinent or it may be for another reason. The point is, PWD don’t always have the same freedom of choice as able bodies do.

Curiosity about disability is a great thing. Take advantage of it.

When children ask about someone who is disabled, it means they want to know more. Children won’t always ask in a sensitive manner, Scott notes. Several times children have asked her, “What’s wrong with your [her] daughter,” but she knows these children don’t have vicious intentions. Take advantage of that curiosity because it’s an opportunity to create a more well–rounded, understanding human.

If people stop listening, stop telling.

Scott emphasizes the balance she’s had to lean between sharing enough and sharing too much. This is an important lesson for children and adults. If someone asks you about your disability or a loved one’s disability, then by all means share with them. However, when they stop listening or start zoning out, cut the conversation quickly. We can’t jam knowledge into people’s minds. They have to want to know.

You can’t pick and choose what people with disabilities you do and don’t accept.

Some of the most hurtful and “disheartening” statements Scott has received is when her friends unknowingly talk about PWD in a negative light and then act as if her daughter is the exception. Parents should teach children to accept all people with disabilities, no matter how mild or severe.

Talk about similarities before differences.

VMI talked about this viewpoint in a previous post on disability etiquette. Whenever discussing a person with a disability to an able–bodied person, begin by highlighting similarities. Sometimes the differences can be so “foreign” to children — like a disabled adult being incontinent — that it scares them off or skews their perception of that person being human. “I talk about the positive things [first],” Scott says, “because if you start off with the ugly parts, [then] the world will think about her in an ugly way.”

Everyone benefits from interacting with people with disabilities.

When parents make the decision to mainstream their child with special needs into a general education classroom, there are numerous benefits to everyone involved. Since Scott put her daughter in a few general education classes with the help of an aide, she has seen an increase in compassion and inclusivity in the classroom among both students and teachers. Scott says hopefully one day one of these classmates will become an advocate for PWD in government, as she sees many of the obstacles her daughter faces as civil rights issues. Additionally, Scott says her daughter’s social skills have improved immensely because of the general education setting. Her daughter functions academically at about a five year old’s level, but her people skills have grown much more mature now.

Awareness fosters understanding, which lowers fear.

If your child asks why he or she needs to learn about disability, explain that without an understanding of people who are different than you, you might come to fear them, hence the word xenophobia. But talking to PWD, befriending them and trying to understand them will lower any chance of fear because you’ll quickly find, as mentioned above, they’re human just like you! By understanding our common ground of humanity, we can progress toward a more inclusive, happy and healthy environment.